One afternoon I was sitting outside the Cafe de la Paix, watching

the splendour and shabbiness of Parisian life, and wondering

over my vermouth at the strange panorama of pride and poverty that was passing before me, when I heard some one call my name. I turned round, and saw Lord Murchison. We had not met since

we had been at college together, nearly ten years before, so I was delighted to come across him again, and we shook hands warmly.

At Oxford we had been great friends. I had liked him immensely, he was so handsome, so high-spirited, and so honourable.

We used to say of him that he would be the best of fellows,

if he did not always speak the truth, but I think we really admired him all the more for his frankness. I found him a good deal changed. He looked anxious and puzzled, and seemed to be in doubt about something.

I felt it could not be modern scepticism, for Murchison was the stoutest of Tories, and believed in the Pentateuch as firmly as he believed in the House of Peers; so I concluded that it was a woman, and asked him if he was married yet.

'I don't understand women well enough,' he answered.

'My dear Gerald,' I said, 'women are meant to be loved, not to be

understood.'

'I cannot love where I cannot trust,' he replied.

'I believe you have a mystery in your life, Gerald,' I exclaimed;

'tell me about it.'

'Let us go for a drive,' he answered, 'it is too crowded here.

No, not a yellow carriage, any other colour--there, that dark green one will do'; and in a few moments we were trotting down the boulevard in the direction of the Madeleine.

'Where shall we go to?' I said.

'Oh, anywhere you like!' he answered--'to the restaurant in the

Bois; we will dine there, and you shall tell me all about yourself.'

'I want to hear about you first,' I said. 'Tell me your mystery.'

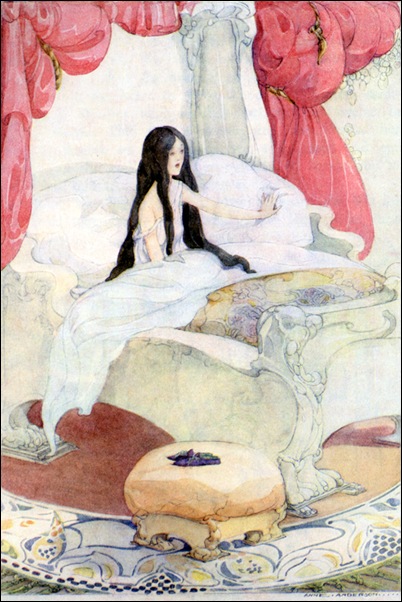

He took from his pocket a little silver-clasped morocco case, and

handed it to me. I opened it. Inside there was the photograph of a

woman. She was tall and slight, and strangely picturesque with her large vague eyes and loosened hair. She looked like a clairvoyante, and was wrapped in rich furs.

'What do you think of that face?' he said; 'is it truthful?'

I examined it carefully. It seemed to me the face of some one who

had a secret, but whether that secret was good or evil I could not

say. Its beauty was a beauty moulded out of many mysteries--the

beauty, in fact, which is psychological, not plastic--and the faint

smile that just played across the lips was far too subtle to be

really sweet.

'Well,' he cried impatiently, 'what do you say?'

'She is the Gioconda in sables,' I answered. 'Let me know all about

her.'

'Not now,' he said; 'after dinner,' and began to talk of other

things.

When the waiter brought us our coffee and cigarettes I reminded

Gerald of his promise. He rose from his seat, walked two or three

times up and down the room, and, sinking into an armchair, told me the following story:-

'One evening,' he said, 'I was walking down Bond Street about five

o'clock. There was a terrific crush of carriages, and the traffic

was almost stopped. Close to the pavement was standing a little

yellow brougham, which, for some reason or other, attracted my

attention. As I passed by there looked out from it the face I

showed you this afternoon. It fascinated me immediately. All that

night I kept thinking of it, and all the next day. I wandered up

and down that wretched Row, peering into every carriage, and waiting for the yellow brougham; but I could not find ma belle inconnue, and at last I began to think she was merely a dream.

About a week afterwards I was dining with Madame de Rastail. Dinner was for eight o'clock; but at half-past eight we were still waiting in the drawing-room. Finally the servant threw open the door, and announced Lady Alroy.

It was the woman I had been looking for.

She came in very slowly, looking like a moonbeam in grey lace, and, to my intense delight, I was asked to take her in to dinner. After we had sat down, I remarked quite innocently, "I think I caught sight of you in Bond Street some time ago, Lady Alroy." She grew very pale, and said to me in a low voice, "Pray do not talk so loud; you may be overheard." I felt miserable at having made such a bad beginning, and plunged recklessly into the subject of the French plays. She spoke very little, always in the same low musical voice, and seemed as if she was afraid of some one listening. I fell passionately, stupidly in love, and the indefinable atmosphere of mystery that surrounded her excited my most ardent curiosity.

When she was going away, which she did very soon after dinner, I asked her if I might call and see her. She hesitated for a moment,

glanced round to see if any one was near us, and then said, "Yes;

to-morrow at a quarter to five." I begged Madame de Rastail to tell me about her; but all that I could learn was that she was a widow with a beautiful house in Park Lane, and as some scientific bore began a dissertation on widows, as exemplifying the survival of the matrimonially fittest, I left and went home.

'The next day I arrived at Park Lane punctual to the moment, but was told by the butler that Lady Alroy had just gone out. I went down to the club quite unhappy and very much puzzled, and after long consideration wrote her a letter, asking if I might be allowed to try my chance some other afternoon. I had no answer for several days, but at last I got a little note saying she would be at home on Sunday at four and with this extraordinary postscript: "Please do not write to me here again; I will explain when I see you." On Sunday she received me, and was perfectly charming; but when I was going away she begged of me, if I ever had occasion to write to her again, to address my letter to "Mrs. Knox, care of Whittaker's Library, Green Street." "There are reasons," she said, "why I cannot receive letters in my own house."

'All through the season I saw a great deal of her, and the

atmosphere of mystery never left her. Sometimes I thought that she was in the power of some man, but she looked so unapproachable, that

I could not believe it. It was really very difficult for me to come

to any conclusion, for she was like one of those strange crystals

that one sees in museums, which are at one moment clear, and at

another clouded. At last I determined to ask her to be my wife: I

was sick and tired of the incessant secrecy that she imposed on all

my visits, and on the few letters I sent her. I wrote to her at the

library to ask her if she could see me the following Monday at six.

She answered yes, and I was in the seventh heaven of delight. I was infatuated with her: in spite of the mystery, I thought then--in

consequence of it, I see now. No; it was the woman herself I loved. The mystery troubled me, maddened me. Why did chance put me in its track?' 'You discovered it, then?' I cried.

'I fear so,' he answered. 'You can judge for yourself.'

'When Monday came round I went to lunch with my uncle, and about four o'clock found myself in the Marylebone Road. My uncle, you know, lives in Regent's Park. I wanted to get to Piccadilly, and took a short cut through a lot of shabby little streets. Suddenly I saw in front of me Lady Alroy, deeply veiled and walking very fast.

On coming to the last house in the street, she went up the steps,

took out a latch-key, and let herself in. "Here is the mystery,"

I said to myself; and I hurried on and examined the house. It seemed a sort of place for letting lodgings. On the doorstep lay her handkerchief, which she had dropped. I picked it up and put it in my pocket. Then I began to consider what I should do. I came to the conclusion that I had no right to spy on her, and I drove down to the club. At six I called to see her. She was lying on a sofa, in a tea-gown of silver tissue looped up by some strange moonstones that she always wore. She was looking quite lovely. "I am so glad to see you," she said; "I have not been out all day." I stared at her in amazement, and pulling the handkerchief out of my pocket, handed it to her. "You dropped this in Cumnor Street this afternoon, Lady Alroy," I said very calmly. She looked at me in terror but made no attempt to take the handkerchief. "What were you doing there?" I asked. "What right have you to question me?" she answered. "The right of a man who loves you," I replied; "I came here to ask you to be my wife." She hid her face in her hands, and burst into floods of tears. "You must tell me," I continued. She stood up, and, looking me straight in the face, said, "Lord Murchison, there is nothing to tell you."--"You went to meet some one," I cried; "this is your mystery." She grew dreadfully white, and said, "I went to meet no one."--"Can't you tell the truth?" I exclaimed. "I have told it," she replied. I was mad, frantic; I don't know what I said, but I said terrible things to her. Finally I rushed out of the house. She wrote me a letter the next day; I sent it back unopened, and started for Norway with Alan Colville.

After a month I came back, and the first thing I saw in the Morning Post was the death of Lady Alroy. She had caught a chill at the Opera, and had died in five days of congestion of the lungs. I shut myself up and saw no one. I had loved her so much, I had loved her so madly. Good God! how I had loved that woman!'

'You went to the street, to the house in it?' I said.

'Yes,' he answered.

'One day I went to Cumnor Street. I could not help it; I was

tortured with doubt. I knocked at the door, and a respectable-

looking woman opened it to me. I asked her if she had any rooms to let. "Well, sir," she replied, "the drawing-rooms are supposed to

be let; but I have not seen the lady for three months, and as rent

is owing on them, you can have them."--"Is this the lady?" I said,

showing the photograph. "That's her, sure enough," she exclaimed;

"and when is she coming back, sir?"--"The lady is dead," I replied.

"Oh sir, I hope not!" said the woman; "she was my best lodger. She

paid me three guineas a week merely to sit in my drawing-rooms now and then." "She met some one here?" I said; but the woman assured me that it was not so, that she always came alone, and saw no one.

"What on earth did she do here?" I cried. "She simply sat in the

drawing-room, sir, reading books, and sometimes had tea," the woman answered. I did not know what to say, so I gave her a sovereign and went away. Now, what do you think it all meant? You don't believe

the woman was telling the truth?'

'I do.'

'Then why did Lady Alroy go there?'

'My dear Gerald,' I answered, 'Lady Alroy was simply a woman with a mania for mystery. She took these rooms for the pleasure of going there with her veil down, and imagining she was a heroine. She had a passion for secrecy, but she herself was merely a Sphinx without a secret.'

'Do you really think so?'

'I am sure of it,' I replied.

He took out the morocco case, opened it, and looked at the

photograph. 'I wonder?' he said at last.

by Oscar Wilde